When you hear the word Brahma, you might think of the three-headed Hindu god of creation and his associated priestly caste the Brahmins. Or you might think of Brahman, the universal goal of reincarnation, where everything eventually returns. But what does that have to do with chickens? Nothing! Brahma Chicken is an entirely different thing, so let’s learn more.

What is Brahma Chicken?

Brahma chicken is a US breed that was developed in the 1800s. It was bred by enhancing the meat qualities of chicken imported from Shanghai, so it’s sometimes known as Shanghai Chicken, Brahmaputra, Gray Chittagong, or Burnham Chicken. The bird initially had more than 12 names before the most common, Brahmaputra, was shortened to Brahma in 1852.

The name change came during a Boston Poultry Show since the judges needed a uniform way to refer to the birds. As for Burnham, it came from George Burnham, who first exported these chickens to England in 1852. At the time, he designated them Gray Shanghaes, gifting nine of them to Queen Victoria. These English birds were tweaked to form Dark Brahmas.

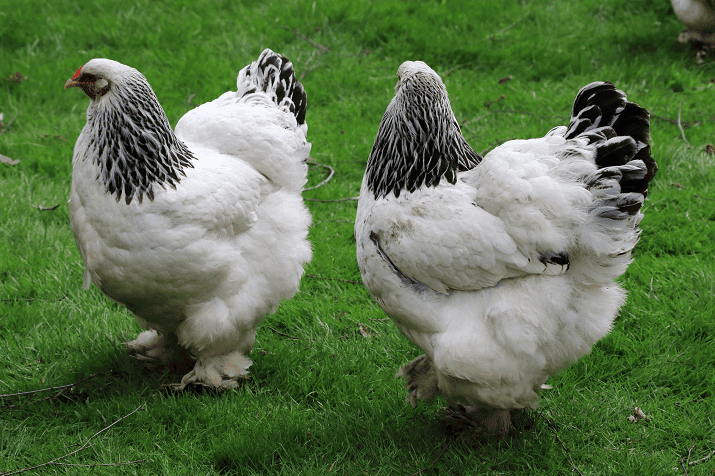

Known as Pencilled Brahmas, these black-and-white speckled birds were later re-exported to the US where they joined two other color lines. Light Brahmas are white with black flecks on their neck, tail, and wing tips. Buff Brahmas have a light brown head and a beige-to-cream body. Buff Bantam Brahmas are more distinctly brown but are much smaller – under 5lb.

Notably, Dark Brahma roosters have a broader color mixture. While the hens are penciled throughout, the roosters have a speckled neck, a white back or saddle, with black on his tail, belly, and chest. Meanwhile, the Australian Poultry Association acknowledges a wider color selection, including blue, crele, partridge, barred, and black plus the other three standards.

The Malay Mixup in Brahma Chickens

The ancestry of Brahma Chickens is said to include grey Malay birds from Chittagong in Eastern Bengal. Today, that region is known as Bangladesh. This Bengali origin story causes confusion because Cochin Chickens were also bred from Shanghai Chicken imports. So it’s possible that Shanghai and Chittagong birds were crossed several times to make Brahmas.

Regardless of their pedigree, Brahmas were kept for meat, and they dominated the United States meat market from around 1850 until the Great Depression. A typical hen weighs about 10lb while a full-grown rooster can grow to 12lb. But they can get even larger, reaching 13lb for hens and 18lb for roosters. These king-sized birds have feathered feet and pea combs.

Their regal bearing fell out of favor around 1930 due to the harsh economic conditions that made it difficult to manage their appetites. Bantams later gained popularity. For reference, Dark and Light Brahmas were officially recognized by the BPS (British Poultry Standard) in 1865 and the APA (American Poultry Association) in 1874. Buff Brahmas came much later.

They weren’t formally accepted until 1924 or 1929, possibly due to the preference for Buff Bantam Brahmas that needed less food and space, making them cheaper to raise. As an aside, the word bantam comes from an Indonesian seaport on Java Island. Bantam was the name of the port, and sailors routinely exported miniature chickens and ducks from there.

Double Mating in Dark Brahma Chickens

Industrial farming was another reason for the eventual 1930 disinterest in Brahmas. Factory farms built crowded coops to rear smaller chickens en masse. These matured much faster, so larger breeds lost out. But for those who still wanted Brahmas, a special technique increased their chances of success. As we noted, Dark Brahma roosters and hens look markedly different.

So breeders use two distinct breeding lines for males and females to ensure the color range stays true. For reference, the two other breeding styles are outcrossing and backcrossing. In outcrossing, you introduce birds from other lineages to widen the gene pool. Backcrossing uses the previous generation to breed the next one i.e. parents or grandparents + offspring.

With single mating, a reliable stud and high-quality hens are used to get male and female chickens. It could also be a specific group that has multiple pairs or trios. But with double mating, you identify pairs that produce good cockerels and pairs that produce good pullets, then you stop them from intermingling and diluting the gene stock. It’s a precise science.

In a double mating system, birds of the ‘wrong sex’ will be sold or slaughtered and won’t be used to breed further lineages. But this system sometimes leads to lower quality chickens all around because a farmer might not have enough resources to sustainably maintain the two groups of breeders. Some may be underfed or under-exercised, reducing overall pedigrees.

Sex and Mating in Brahma Chickens

Backcrossing and outcrossing describe the individuals that mate while single mating and double mating are about the number of breeding groups. So there’s a third category here – spiral or clan mating. This is when you have multiple breeding lineages. You start with three to five quality roosters and rotate them among hens raised with their mothers and sisters.

This works best in a flock that already has established characteristics, since the gene pool stays consistent. But let’s go back to the beginning. Brahma chicks cost about $5. But since they get so big, they need lots of food and can get aggressive if they’re underfed. They also take a long time to mature. Brahmas rarely start mating or laying eggs before 7 months.

In comparison, most breeds start at 5 to 6 months, and some like Egyptian Fayoumis are ready at just 4 months. And since Brahmas needs lots of space to run around, they’re happier if your free-range them. But their bulky bodies minimize their flapping distance so they can’t lurch very high. When you build roosts and perches for them, they’ll have to be placed lower.

Although this breed is ridiculously gentle, it can look mean and intimidating due to its strong beak and beetle brow. And it’s tough to tell hens from roosters because they mature so late. Boys eventually develop bigger combs and wattles than their sisters, as well as hackles and tail sickles – the long, deeply curved feathers on a rooster’s tail. But these take 5 to 6 months.

Egg-Laying in Brahma Chickens

While the Brahma is mainly a meat bird, it’s good for eggs as well, since it’s one of the few breeds that can produce eggs in winter. Most chickens molt in the fall and recover during the icy months. Molting is when a bird sheds its old feathers and grows new ones, and it doesn’t usually mate or lay eggs during these 8 to 16 weeks of mandated seasonal self-care.

But Brahmas still lay eggs in the winter, and they can produce up to 200 large mid-brown eggs every year. Most of these eggs pop out from October to May, which is a slow period for other breeds. That said, Brahmas only lay 3 to 4 eggs a week. Since they don’t mind the cold, they make up the deficit by laying during the cold months when other breeds are on a break.

If you time it right, you can effectively tag-team them with spring and summer layers. That said, the only breed that’s larger than a Brahma Chicken is a Jersey Giant, so they need lots of space. But Brahmas have such a gentle temperament that they’re perfect for kids. Their calm nature and high productivity make them the ideal dual-purpose breed for beginners.

Their size is also helpful in fending off small predators like rats and weasels. Toss in some adult guinea fowls and your flock will be quite well-protected. But these big birds don’t brood well, so you can also include some silkies to help hatch your Brahma eggs. This is why mixed-breed backyard flocks are such a good idea. But check the rooster proportions to avoid fights.

Keeping Your Brahmas Healthy and Happy

Most Brahmas grow 30” tall – that’s two and a half feet! But Buff Bantam Brahmas are the easiest miniature breed to find, with light and dark bantams being much rarer. And speaking of feet, the feathers on a Brahma Chicken’s legs are only on the outer toes. The two inner toes are usually bare and exposed. But those feathered feet are tough to maintain in muddy areas.

That said, the feathers are helpful in wintry weather. But because Brahmas carry so much of their weight in their plumage, they can sometimes struggle in warmer months. That’s why egg production slows down in spring and summer. Free-range your Brahmas as much as possible, ensuring they have cool, fresh water and lots of shady spots to get out of the sun.

Since they can barely fly and are too heavy for hawks and other aerial predators, you don’t need to cover the coop unless you have a mixed flock. If you’re only keeping Brahmas, a two to three foot fence is high enough to keep them protected. But if they’re foraging in enclosed areas make sure there’s enough vegetation and insect life to keep them fat, fed, and happy.

Otherwise, Brahmas tend to get ‘hangry’ and may start hassling each other. But they’re quite friendly in general and may beg for touches and treats, even though they’re too big to fit on your lap. Free-ranging is a good way to raise healthy birds because their heavy bodies could easily get obese if they’re sedentary. Place lots of stimulating toys inside their coops as well.

The Trouble With Brahmas and Cold Feet

Brahmas are rather large in their adult form, but their chicks are just as small as any other breed. So when a mother occasionally gets broody, you’ll need to supervise her so she doesn’t accidentally trample her hatchlings and squish her babies. This problem doesn’t come up often since Brahma hens are rarely broody. But to be on the safe side, hand the new eggs off.

You can give them to a silkie who is smaller and far more nurturing. Silkies are extremely broody and are happy to hatch and raise the babies of other hens. Even roosters are likely to tidbit, which is when a rooster finds a tasty treat, fusses to attract the attention of hens and chicks, then drops the treat where they can see it. This teaches the babies what’s good to eat.

The only other issue you may find with Brahma Chickens is scaly leg mites. This breed is more susceptible because the mites, lice, and other parasites can hide inside their feathered feet. Also, during the winter, while the feathers will warm the outer legs, the exposed inner feet may get frostbite, mostly from the mud, poop, and muck that accumulates on their feet.

The feathers themselves can also get clumps of dirt, and any moisture in this mess can freeze and cause injury. One suggestion is to give the birds a warm foot bath and massage. But be sure to dry their feet immediately or you’re just providing additional sources of icy feet. Their pea combs are fine since they’re so small. The limited surface area is unlikely to get frostbite.

Important Dimensions for Raising Brahmas

In addition to low roosting perches no higher than a foot, Brahma Chickens do better with enlarged nesting boxes, since both their bodies and their eggs are above average. 14” by 14” is a good size for laying, since hens tend to share boxes. You only need one box for four or five hens and if you add more, they’ll stay idle and unused. Also, one rooster can serve 10 hens.

To keep their feet clean and reduce your feather-fluffing duties, use stone or sand for coop flooring. You can still have a cordoned-off dust bath for chicken spas. One simple solution is to place a large tractor or trailer tire in one corner, erect a shade or roof over it, and fill it with loose soil. Change this dust regularly to keep it dry and prevent it from getting muddy.

Back in the 1850s, as Shanghais and Chittagongs became Brahmas and Cochins, Hen Fever pushed their prices from $15 to $150! Today, they’re more common as backyard birds since they’re impractical for large-scale industrial farming. But they do face the risk of bumble-foot (infection when their weight presses in a small object), fowl cholera, and Newcastle fowl pox.

A Royal Chicken by Any Other Name

T. B. Miner was a chicken aficionado from the 1850s who published a magazine called The Northern Farmer. While reporting on the Boston Poultry Show of 1852, he ran out of space and typed Brahma instead of Brahmaputra, a river near this breed’s original birthplace. Do you know any other fun facts about Brahma Chickens? Tell us in the comments below!